This middle grades retelling of the classic fairytales: Rapunzel, Cinderella, and Sleeping Beauty, replaces white characters with diverse Desi characters, reclaims female characters’ empowerment, and weaves the stories together with Rumaysa first freeing herself, and then using a magic necklace that takes her to those in need (Cinderayla and Sleeping Sara) in her quest to find her long lost parents. After a few chapters, I started writing a list of gaping-huge-ginormous plot holes, they are frequent and laughable, then I took a deep breath and recalled the similar eye-rolling inconsistencies that plague perhaps all fairy tales, but specifically Disney-esque ones. Once I let go of trying to understand why Rumaysa is wearing hijab while locked in an isolated tower, or how the witch can’t remember her name, but Rumaysa knows the name her parents gave her when she was kidnapped on the day of her birth, or that she knows she was kidnapped and her whole backstory, just to name a few, the book was much more enjoyable. I still have major issues with some of the forced Islamization and cultural tweaks, but not because they existed, but rather because they weren’t strong enough. Why have an Eid ball for all the fair maidens in the land. It was awkward to read all the young people showing up to pair off, and then people asking the prince to dance, and him saying he didn’t know if he could. Why not just make it an over the top Desi wedding with families, where dancing and moms working to pair their kids off is the norm. Having it be a ball for the maidens in the land, just seemed like it was afraid to commit to the premise of twisting the fairytales completely. There are a few inconsistencies, however, that I cannot overlook. This is a mainstream published books and there is at least one spelling error and grammar mistake. I could be wrong, as it is British, and I am by no means competent in even American English, but I expect better. Even content wise, Prince Harun for example, is wearing a mask, but the text comments on his blushing cheeks, eyes, eyelashes, and smile, not a typical mask perhaps? And don’t get me started on the illustrations, the same awkward ball has Ayla leaving, and in the picture not wearing a mask concealing her face as the text states. Overall, the inside illustrations are not well done. The cover, by artist Areeba Siddique is beautiful with the shimmery leafing on the edges, that would have brought the inside pages a lot more depth and intrigue than the ones it contains. Despite all the aforementioned glimpses of my critiques to follow, I didn’t hate the book and quite enjoyed the light handed morals and feminism that was interwoven with clever remarks and snark. The first story has Rumaysa wearing hijab, finding a book about salat and praying. The second story takes place on Eid and Ayla eats samosas, discusses Layla and Majnun, and has a duputta. The third story I don’t recall any culture or religious tidbits other than keeping with the consistency of cultural names. There is mention of romance between an owl who has a crush on a Raven, but the heroines themselves are learning to be self sufficient from errors of their parents/guardians and are not looking for any males to save them. Other than that the book really needs an editor and new illustrations, I can see fairytale loving middle grade kids reading the book and finding it enjoyable, or even younger children having it read aloud to them a few chapters at a time, and being drawn in to the stories and eager to see what happens next. It would work for that demographic, but perhaps no one else.

SYNOPSIS: (spoilers)

Rumaysa’s parents steal vegetables from a magical garden when there is no food or work to be found, as a result when Rumaysa is born, the owner of the garden, an evil witch, takes Rumaysa and places her in a tower protected by an enchanted forest and a poisonous river. No one can get in, and Rumaysa cannot get out. In the tower Rumaysa reads, no idea how she learned, and spins straw in to gold as she sings a song that channels the magic she consumed in utero from the stolen garden. With only rations of oats to eat, a friendly owl named Zabina frequents Rumays daily and brings her berries and news . When he brings her a new hijab, Rumaysa has the idea to lengthen the hijab with bits of gold over time, so that she might escape. When she finally gets her chance, she is met by a boy on a magic carpet named Suleiman, and is both shocked and annoyed that someone got close to the tower, and only after she saved herself. The two however, and Zabina, are caught by the witch and must escape her as well. When that is all said and done, Suleiman gives Zabina a necklace that takes one to someone in need of help. His parents want him to save a princess, he wants to study in his room, so he hands off the necklace hoping it will help Rumaysa find her parents, and he heads off on his flying carpet.

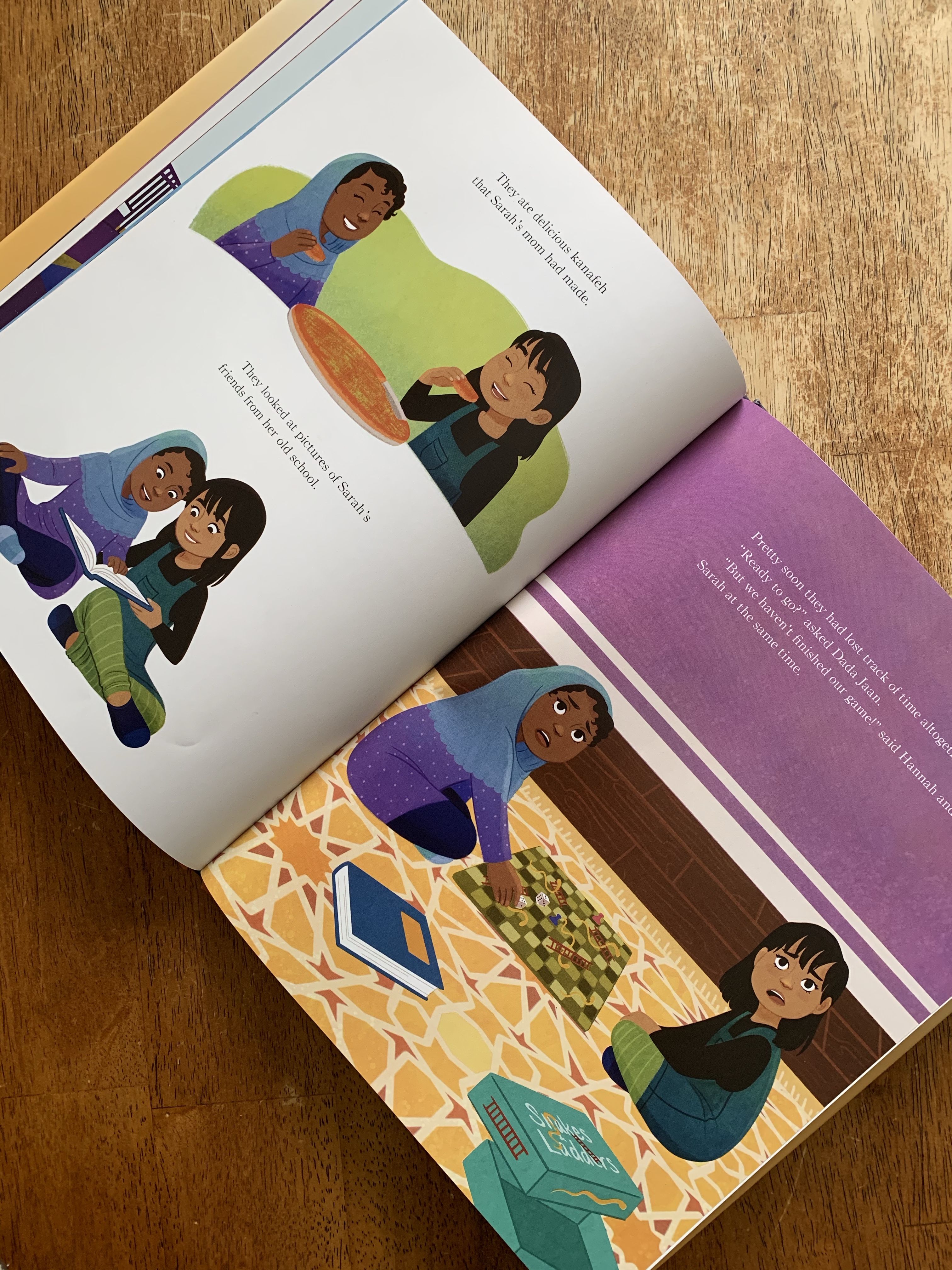

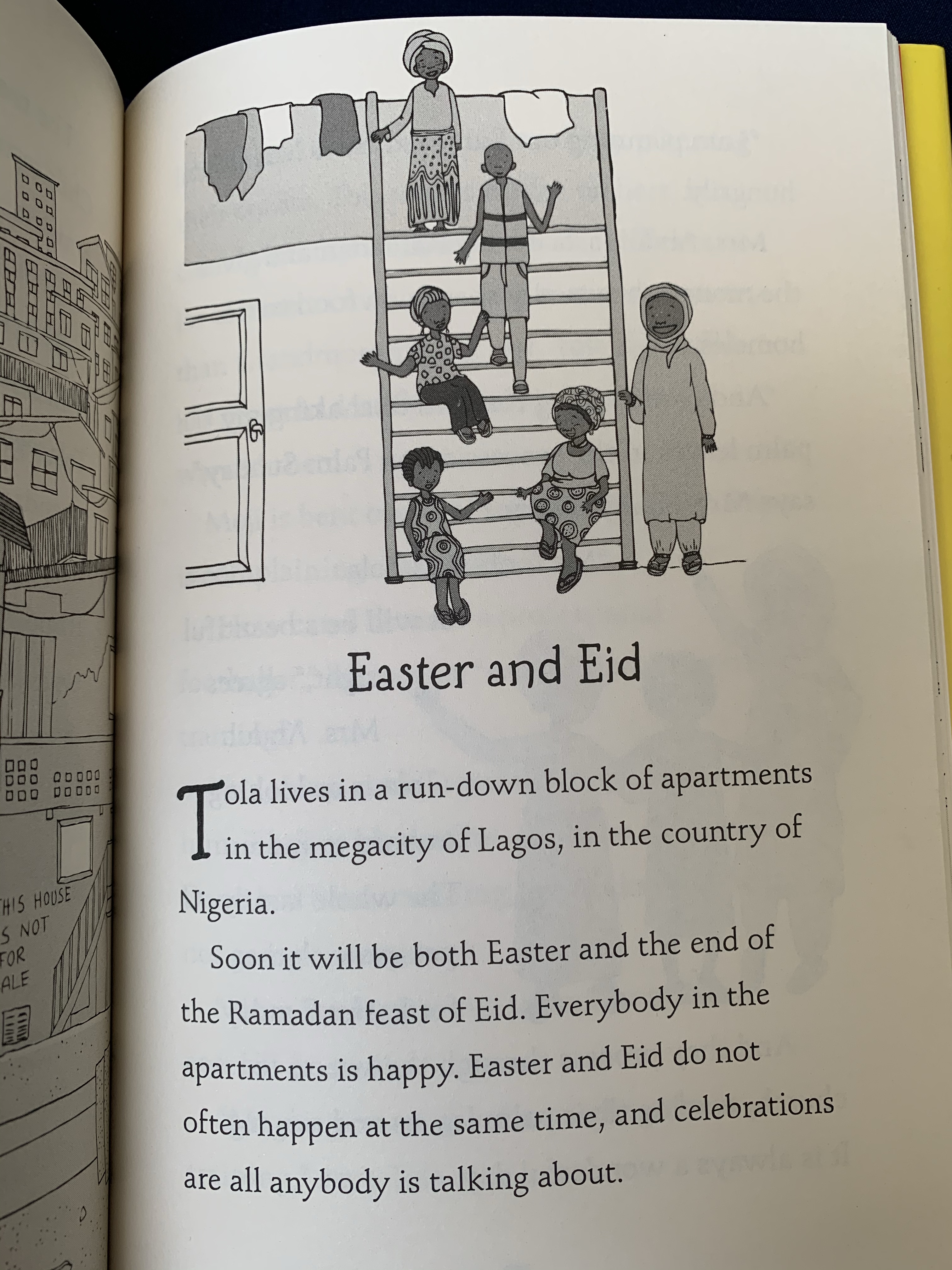

The necklace doesn’t transport Rumaysa to her parents, however, it takes her to a street where a girl is throwing rocks in desperation having been denied attending an Eid ball after her dress was torn to shreds. The story starts with Ayla’s back story before Rumaysa arrives, but the two girls befriend each other, Rumaysa uses her magic gold weaving abilities to conjure up a new and beautiful dress and golden shoes and the girls head to the ball. When Ayla heads off to get samosas she meets the prince, but doesn’t know he is the prince. They argue about the play Layla and Majnun and when her stepmother asks about the dress, Rumaysa and Ayla make a run for it. A shoe is lost, the stepmother comes to know, the guards search for the missing girl, and all is well. Except Harun is incredibly shallow and superficial and only interested in Ayla’s clothes and status, so she rejects him and points out that she is much too young for marriage. She instead reclaims her home, fixes her relationship with her stepsisters and begs Rumaysa to stay. Rumaysa makes her excuses and is whisked away to a land that is being ruled by a man and his dragons.

Originally the land of Farisia is ruled by King Emad and Queen Shiva, but they have become unjust and disconnected from their people. When Azra gets a chance to steal Princess Sara and take the kingdom, he does. Rumaysa arrives to free a sleeping Sara from the dragon and restore apologetic and reformed leaders to the thrown.

WHY I LIKE IT:

I do like the spinning of familiar stories and either updating them, or twisting them, or fracturing them, so I am glad to see an Islamic cultural tinge available. I feel like the first story was the strongest conceptually even if the details and morals weren’t well established. The second story was strong in the messaging that Ayla, and any girl, is more than just a pretty dress, but the premise was a little shaky and not that different from the original. The third story was a little lacking developmentally for me and all three I felt could have gone stronger in to the religion and culture without alienating readers or becoming heavy. There are characters illustrated in hijab, some in saris, some in flowing robes. Princess Sara is noted to be a larger body type and I appreciated that in elevating the heroines, other’s weren’t put down. Even within the book, there is diversity which is wonderful.

FLAGS:

There is lying and stealing with consequences. “Shut up” is said. There is magic, death, destruction, and a brief mention of an avian crush.

TOOLS FOR LEADING THE DISCUSSION:

I could see this being used in a classroom for a writing assignment to urge students to write their own tales. I think it is fourth or fifth grade that children read fairytales from different points of view: think the three little pigs from the wolf’s perspective or the Stinky Cheese Man and Other Fairly Stupid Tales, and this book would lend itself easily to that lesson as well.