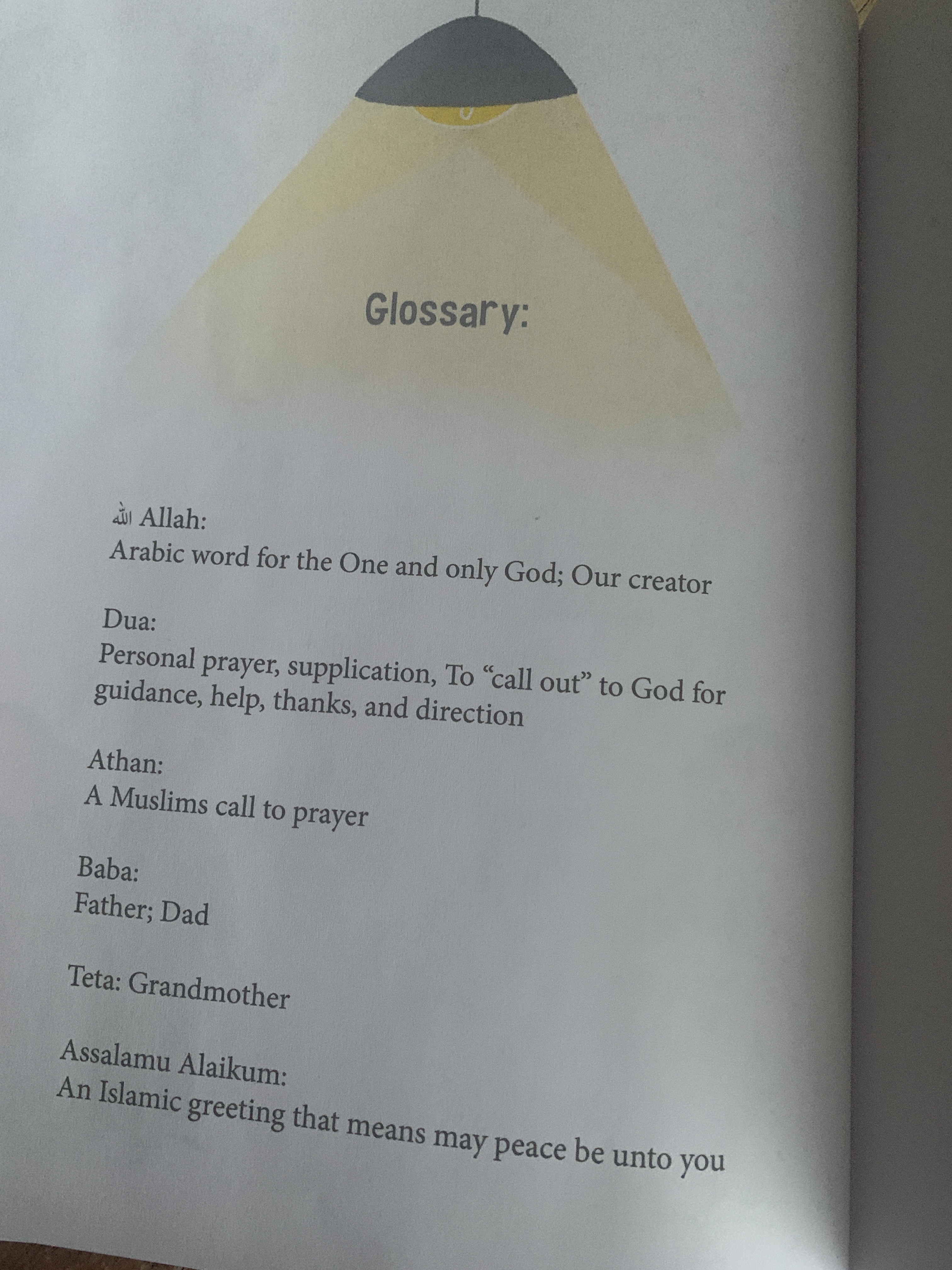

This adorable 40 page book will be a great read to classrooms to see Ramadan in action from a little girl trying her best to fast and pray without internalized Islamophobia or info dumps cluttering a flimsy plot. The bright illustrations bring the story to life and will captivate preschool to early elementary readers and listeners. The story shows the religion and leans into the concept of Taqwa as a reason for fasting, something to strive for, and prompting the little girl to give to her community. There is a robust backmatter with sources, a glossary, two crafts, and information about Ramadan, taqwa, moon and stars, and being mindful. It should be my favorite Ramadan book ever, with when we start fasting correct, adding a twist to the trope of a first fast, and centering Islam- unfortunately, the story tries to do a lot, too much in fact, resulting in the book missing the emotional element that makes Ramadan stories memorable and beloved. I think the author’s style is also something subjective that I just don’t vibe with, so while I will provide rationale for my opinions as I continue my review, I am aware that fans of her previous books, will absolutely fight me on my thoughts, which I welcome. Even with my critiques, I’m glad I preordered the book and have spent time reading and sharing it.

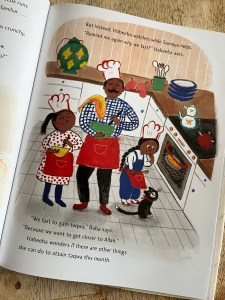

The book starts with Habeeba’s kitchen busing with activity in the dark morning. The first day of Ramadan has Baba and his two daughters eating and planning a month of fasting every day and praying taraweeh every night. Big sister Sumaya encourages Habeeba to come to the library at lunch time. Once at school the teacher reads a Ramadan story, in the library, the librarian encourages Habeeba with stickers, and the two sisters look at books together.

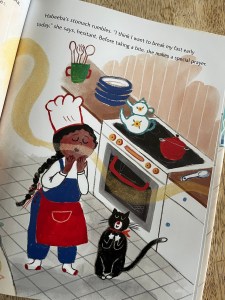

Once back home though, chef Baba’s kunafa tempts Habeeba. Baba reminds her that fasting is to gain taqwa, “because we want to get closer to Allah.” Habeeba starts to wonder what else she can do to gain taqwa, but the thought seems lost as she makes a special prayer, and breaks her fast early.

Later at the masjid, the little boy in front of Habeeba makes focusing on duaa hard, and when she is in sujood, she finds herself drifting off to sleep. Day after day she struggles with the temptations of delicious treats, and slipping off to sleep in the comforts of the masjid at night.

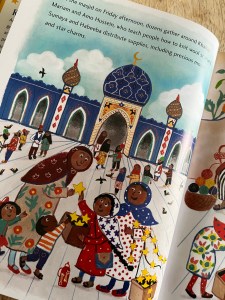

The last week of Ramadan, Habeeba breaks down to Sumaya who tells her she is doing great, and that remembering Allah “also means being mindful of their community.” Together they plan to participate in a service project to help the community and give back. Before the end of the month, Habeeba fasts a whole day and with her family’s encouragement, hopeful that in time she will fast everyday and stay awake in prayer.

The first page did not set the tone as a polished read, I am terrible at grammar, but “like watermelon, pomegranates, and homemade muffins.” What foods are like watermelon and pomegranates, those are the foods on the table, so maybe “such as” or drop the comparison word all together and just say what is on the table and what we are seeing in the illustration. Throughout it felt like sentences were choppy, and when read aloud commas were missing. The diction also seemed off to me in describing taqwa, not wrong, just stilted and not relatable to the demographic as it is stated, but not really shown. Do six year olds understand mindfulness? It goes from fasting is to gain taqwa, because we want to get closer to Allah, to it being hard to concentrate and practice mindfulness, to “Remembering Allah during Ramadan also means being mindful to their community.” The backmatter says “Taqwa is achieved by being mindful of Allah and remembering to do one’s best every day- especially during Ramadan.” I feel like words and phrases are being used interchangeably and not in a way that connects dots of understanding for the reader. A bit more on level articulation is needed. And I know I don’t like exposition, but it needs smoothing out and clarity. A few signposts to tie back to the theme, with word choice that kids will understand. They don’t need to be hit over the head that fasting and praying and charity is worship, but they should grasp that little Habeeba is pushing herself to keep trying day after day to gain taqwa. Perhaps if Baba at the end would have been proud of her efforts to keep trying instead of saying, “I am most proud of you for sharing Ramadan with everyone.” The point of Ramadan and taqwa would have come through. I realize it needed that line to make the title make sense, but honestly that is not what the book is about. Only four pages address the community. I have no idea why the first day Habeeba wonders about other ways to get closer to Allah swt, sidenote there is no attribution in the story or backmatter, and it is abandoned until the end of the book and the last week of the month. It very easily could have been threaded in and would have fleshed out the title and the different aspects of Ramadan, growing closer to Allah, and finding ways to help the community.

I did love the school community, from the teacher to the librarian, it is delightful to see support from the larger community in our lives, and models how simple and easy it can be to create a safe and encouraging environment. The relatability of the characters being so excited and ambitious the first day, going back to sleep after fajr, finding distraction annoying, and getting so tired during salat was also relatable. To be seen in such familiar acts will bring smiles to readers and reassurance that we are all so very similar in so many ways.

I felt the star and moon motifs were overdone for no effect, what even are “moon and star charms?’ It seemed tropey and superficial, same with the goody bag and the beginning being a sign of babies and then lovingly embraced at the end. If meant to show the sisters relationship coming full circle it missed the mark for me, as truthfully I didn’t find the sisters relationship to be a proper characterization of the story at all. Habeeba compares herself to Sumaya, wanting to be as good as her, but Sumaya is rather kind and just used as a foil. She spends time at the library with her, encourages her and helps her. It is not a sibling relationship focused story, and adding a crumb here and there, just seemed like the book didn’t know where it wanted to go.

Had the book not been checked by a named Shaykh who consulted on the story, I’d be a little more worried about the messaging that we fast for taqwa and not that we fast because Allah swt commands it, and that when we do fast we foster that closeness to Allah. I also found it odd that the backmatter says Ramadan is “set during the ninth month.” Ramadan is the ninth month.

The first reading or two will be joyful and fun, I have no doubt, few will read it as often as I did. I also doubt anyone will take the time to be this critical. But I do hope at the very least, if you have a little one trying to fast, you will not have tempting treats and desserts out every afternoon after school. And that you did notice the one day she wasn’t home, Habeeba was able to complete her first fast.

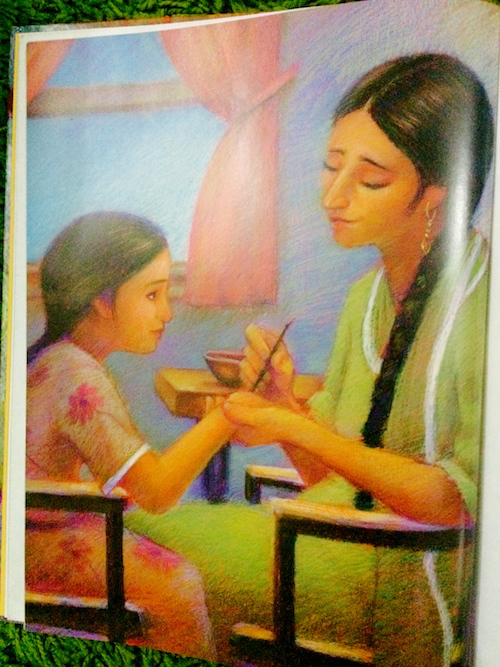

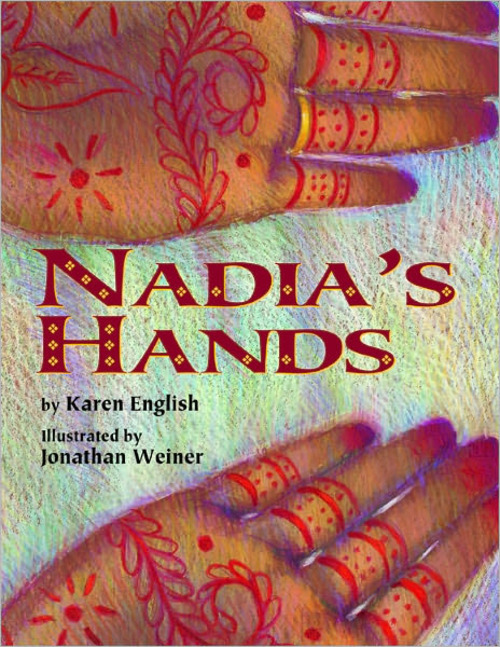

Nadia’s aunt is getting married and she gets to be the flower girl in the Pakistani-American wedding. She also will get mehndi put on her hands for the big event. Her cousins warn her that she might mess up and even in the midst of her excitement she begins to worry what the kids at school will say when they see her hands on Monday. As her aunt prepares the mehndi and the application process begins, various uncles peek in on her and her aunt gifts her a beautiful ring. The mehndi has to sit on the skin for a while to set and as Nadia practices sabr, patience, I couldn’t help but think something seemed off in the story. I’ve been at, in, and around a lot of Pakistani and Pakistani-American weddings, and this story didn’t seem to reflect the tone of such occasions. The book doesn’t reflect the hustle and bustle and near chaos, it doesn’t sound like the tinkle of jewelry and laughter as the women sit around chatting and getting mehndi put on together, the pots on the stove are referenced but not described so that the reader can smell the sauces thickening and hear the pans crashing and taste the deep rich flavors. It is lonely. Nadia is lonely and filled with anxiety about Monday. Durring the wedding she is walking down the aisle and suddenly freezes when she looks down and doesn’t recognize her hands. Her cousins seem to show unsupportive “I-told-you-so” expressions as she searches for some comforting encouragement to continue on. When she finishes her flower girl duties, her grandma asks if she understands why looking at her hands makes her feel like she is “looking at my past and future at the same time.” Nadia doesn’t understand and the author doesn’t explain. At the end she is ready to embrace that her hands are in fact hers and that she will show her friends on Monday. But the reader has no idea how it goes, or what exactly the significance of her painted hands are. The book fails to give any insight or excitement for a culture bursting with tradition at a time of marriage.

Nadia’s aunt is getting married and she gets to be the flower girl in the Pakistani-American wedding. She also will get mehndi put on her hands for the big event. Her cousins warn her that she might mess up and even in the midst of her excitement she begins to worry what the kids at school will say when they see her hands on Monday. As her aunt prepares the mehndi and the application process begins, various uncles peek in on her and her aunt gifts her a beautiful ring. The mehndi has to sit on the skin for a while to set and as Nadia practices sabr, patience, I couldn’t help but think something seemed off in the story. I’ve been at, in, and around a lot of Pakistani and Pakistani-American weddings, and this story didn’t seem to reflect the tone of such occasions. The book doesn’t reflect the hustle and bustle and near chaos, it doesn’t sound like the tinkle of jewelry and laughter as the women sit around chatting and getting mehndi put on together, the pots on the stove are referenced but not described so that the reader can smell the sauces thickening and hear the pans crashing and taste the deep rich flavors. It is lonely. Nadia is lonely and filled with anxiety about Monday. Durring the wedding she is walking down the aisle and suddenly freezes when she looks down and doesn’t recognize her hands. Her cousins seem to show unsupportive “I-told-you-so” expressions as she searches for some comforting encouragement to continue on. When she finishes her flower girl duties, her grandma asks if she understands why looking at her hands makes her feel like she is “looking at my past and future at the same time.” Nadia doesn’t understand and the author doesn’t explain. At the end she is ready to embrace that her hands are in fact hers and that she will show her friends on Monday. But the reader has no idea how it goes, or what exactly the significance of her painted hands are. The book fails to give any insight or excitement for a culture bursting with tradition at a time of marriage.